May 10, 2022

The Port of Rotterdam, in collaboration with exporting countries and domestic companies, has promised to triple its low-carbon hydrogen supply to northwest Europe by 2030 in a nod to the region’s heightened need for energy independence and decarbonisation.

The plan, which was announced on May 10 at the World Hydrogen Summit being held in Rotterdam, could cement Rotterdam’s position as a key energy hub – especially for hydrogen – in northwest Europe. The port’s collaborative initiative is key in building international supply chains needed for hydrogen trading and pricing to develop.

OPIS interviewed international hydrogen supply chain manager Martijn Coopman and spokesperson Sjaak Poppe on the feasibility of the port’s ambition despite high costs, poor infrastructure and lack of a common global standard for low-carbon or renewable hydrogen.

OPIS: The Port of Rotterdam announced today that it will be supplying 4.6 million metric tons of hydrogen to Europe by 2030 in collaboration with exporting countries and domestic companies. This is a sharp increase. Why have volumes gone up in this latest estimate?

Poppe: That is because the number of hydrogen projects are going up all the time. We had set up an energy transition program five to six years ago. At first, we didn’t pay any attention to hydrogen. Hydrogen was supposed to be something that took off sometime in the 2030s. And four years ago, we had just one or two people looking at hydrogen. But now, we have 20 people on hydrogen. So, that’s how fast it’s taking off.

OPIS: How did you curate the list of countries that could export to Rotterdam?

Coopman: Two years ago, we had come out with a graph showing a potential demand of 20 million mt by 2050. In 2030, demand was expected to just be over a million mt from half a million mt now. But most of it was expected to be produced locally and imports were not meant to play a role until after 2030.

But we just said – why don’t we go out and find out where the supply will come from. That threw up a list of 15 potential exporting countries back then. The good news is - there’s a diverse portfolio of hydrogen sources and a fair distribution of countries that can benefit from these new international supply chains.

Poppe: We explored what could be hydrogen exporting countries in the future. Because in this part of the world, there is high energy consumption. But there are many parts of the world where you could produce electricity and hydrogen much cheaper. And when news got around that Rotterdam is trying to set up import trade links, the phones started ringing.

OPIS: Did the war in Ukraine accelerate the hike in your supply targets?

Poppe: The EU’s RePowerEU calls for a four-fold increase in supply in eight years’ time. The outreach we’ve done among companies and countries shows this ambition is achievable. These are all companies and countries working on concrete projects. I won’t be surprised if, in two years’ time, 4.6 million mt ends up on the lower side. It all depends very much on E.U. regulations. We have two aims now, it’s not just climate change but also energy independence, which could trigger the whole hydrogen economy.

"The good news is - there’s a diverse portfolio of hydrogen sources and a fair distribution of countries that can benefit from these new international supply chains."

~Martijn Coopman

OPIS: Would you be prioritizing green hydrogen supply?

Poppe: Most of the volumes would be green, but some of it will be blue. About 0.25 million mt would be local green hydrogen and 0.35 million mt local blue. And four million mt will be imports. We’re co-operating with a company in the north of Norway and they’re looking at producing blue ammonia.

Coopman: But there’s more blue sources. In the Middle East: Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia. Also, in Texas. Potentially, we’ll even source blue hydrogen from Australia.

OPIS: Will having blue hydrogen in the supply mix prevent the transition towards green?

Poppe: I do not see it as a problem. You’ll have a bigger market and larger supply with blue, and it will help the hydrogen economy take off.

Coopman: We’ve to be realistic. If we have these ambitious targets, we can’t stick only to green.

OPIS: Your supply partners also highlighted the need to get their green hydrogen exports certified as green by the E.U. Everyone’s hoping there will be a common certification standard – do you envision the same?

Poppe: Things are looking fine on that front, but if it doesn’t happen, there’ll be serious problems.

OPIS: A buyer in Europe would want to know not just the carbon intensity of hydrogen produced elsewhere, but the carbon footprint of bringing it all the way to the Port of Rotterdam.

Coopman: That is why there is so much co-operation between European certification initiatives and the Australian and the Chilean and the U.A.E. certification initiatives. They do the certification on the production side and the export side. It needs to link in with what in Europe the off-takers would like to see. Need to see, in fact. That is important because they need to then present that in turn to their customers or an institution that compensates them for it being sustainable.

The international co-operation between certification bodies is therefore super critical. There are quite a number of initiatives and they’re converging together, although they have slightly different approaches. There is no ultimate correct answer. It’s about getting it as close to a right answer as possible.

"The EU’s RePowerEU calls for a four-fold increase in supply in eight years’ time. The outreach we’ve done among companies and countries shows this ambition is achievable."

~Sjaak Poppe

OPIS: How can the cost gap between blue and grey hydrogen be narrowed? Will the Dutch government subsidies work?

Coopman: There is the Porthos project, which is our carbon capture and storage (CCS) project, which allows grey hydrogen to turn into blue hydrogen. The contracts for difference scheme is not granted to us but granted to the first customers of the Porthos system. Those are the first four hydrogen producers. They will get these contracts for difference subsidies to ensure that the business case of blue is equal to grey.

Poppe: As long as the ETS price is below the cost price for CCS, they will get the difference annually for the next 15 years, which is the period of the Porthos project.

OPIS: The main problem in moving hydrogen around locally is the lack of a pipeline network. Gasunie’s Hynetwork Services is working on solving that in this region. But, internationally, what type of hydrogen carrier would be best suited to the task of your ambition to import four million mt?

Coopman: We’re agnostic on that – it is the industry that will decide. However, we’ve done our research on what is the preferred carrier. There are carriers that are very much suited to certain end uses and others that are suited to other end uses. In the Port of Rotterdam, as well as in the hinterland, we have all types of end users. We therefore believe we will have all types of hydrogen carriers arriving in Rotterdam.

At the moment, we have five new ammonia terminals, on top of the existing one from OCI, two Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs) initiatives and two liquid hydrogen initiatives in the study phase. By 2030, we will have all these three types of carriers available at the Port of Rotterdam. If you want to import four million mt, you’re going to need multiple terminals: we estimate at least ten terminals.

OPIS: What ships would you use to transport these hydrogen carriers?

Poppe: We can’t use the same ships or tank storage as liquid natural gas (LNG). So, you’ll have to develop new ones. That’s why the industry thinks ammonia will be the first carrier to be used.

OPIS: Would you be taking that ammonia and converting it back to hydrogen here at the port?

Poppe: If the industry needs ammonia for fertilizers, then you don’t need to convert it. But otherwise, there would be a cracker next to the ammonia import terminal to convert it to hydrogen.

OPIS: There’s been some talk of the use of hydrogen as a marine fuel. When would you see a 5% market share for hydrogen in marine fuels?

Coopman: I think it’s a great question. We’ve been asking ourselves that question. Whether we should go into that. We’re getting ready. We’ve already done a methanol bunkering demonstration last year.

We’re now heavily working with a whole consortium of companies on an ammonia bunkering demonstration in two years’ from now. As soon as the first ammonia-fired ship sets sail, its first route would likely be from Rotterdam to another port. We’ll have the regulations in place, the safety procedures in place. So, we’re getting ready for it.

An interesting aspect is that, if you take ammonia instead of diesel and you’re sailing the same distance, you need a larger tank. The big question is – do you use the same ship and sacrifice some of the cargo space? Or change the ship? Or do you do additional bunkering on the way?

--Interview by Cuckoo James, cjames@opisnet.com

--Editing by Rob Sheridan, rsheridan@opisnet.com

Photo Credit: Danny Cornelissen and the Port of Rotterdam

© 2022 Oil Price Information Service, LLC. All rights reserved.

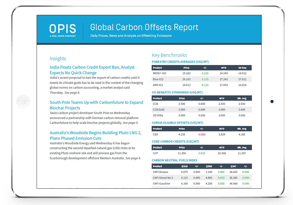

OPIS Global Carbon Offsets Report is the world's first voluntary carbon markets price report, meeting the demand for price discovery and transparency across the industry. It provides daily physical assessments for 27 voluntary carbon offset credits and 10 compliance carbon offset credits, including REDD+, CORSIA Eligible Offsets, and California Carbon Offsets. Breaking news coverage and analysis reveals trends and fundamentals impacting global voluntary carbon market supply and demand.

OPIS Global Carbon Offsets Report is the world's first voluntary carbon markets price report, meeting the demand for price discovery and transparency across the industry. It provides daily physical assessments for 27 voluntary carbon offset credits and 10 compliance carbon offset credits, including REDD+, CORSIA Eligible Offsets, and California Carbon Offsets. Breaking news coverage and analysis reveals trends and fundamentals impacting global voluntary carbon market supply and demand.

Try the OPIS Global Carbon Offsets Report free for 10 days!

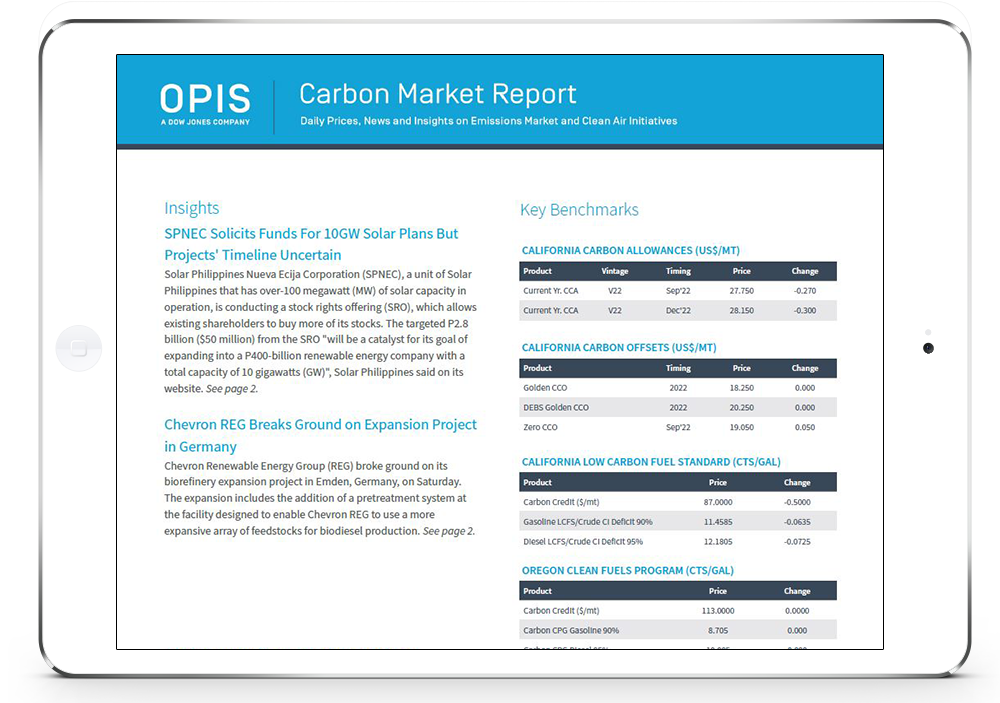

OPIS Carbon Market Report assesses the largest compliance carbon markets in the world with reliable and transparent trade-day data. The report provides comprehensive carbon coverage with transparency for over 100 indices, include prices for California Carbon Allowances, California Carbon Offsets, Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative Allowances, U.S. Renewable Energy Certificates, California Low Carbon Fuel Standard, Oregon Clean Fuels Program, and the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard. Easily track and manage your carbon compliance costs with daily pricing and breaking news.

Try the OPIS Carbon Market Report free for 10 days! You’ll get a daily PDF pricing report and real-time news alerts.

OPIS, A Dow Jones Company

© 2025 Oil Price Information Service, LLC. All rights reserved.